There's no experience that compares to the first time the blues get to you. The hairs on your neck stand up and an uncanny churning sets up between your heart and your stomach. It's the universal experience that unites the blues world.

Today that world is wide open. The fences are down. The boundaries have been extended to take in the music's lovechild, rock & roll, and through the disciples of Muddy Waters and B.B. King, Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley, the experience continues, though with the accent on a battering-ram intensity of sound, not nearly as convincingly as it might. But the important thing is that it keeps on happening.

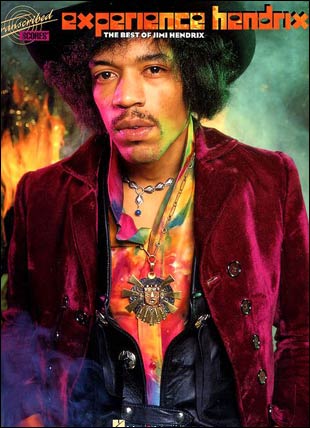

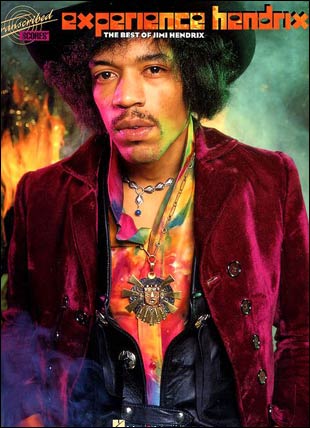

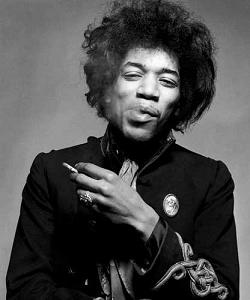

Right now, across the Atlantic, a unique blues experience is taking place--the Jimi Hendrix Experience, a marriage between a couple of British rock merchants and an American Negro.

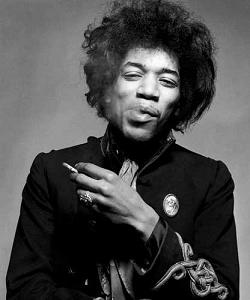

Although he has been adopted by the British faction of the flower-power syndrome as a kind of high priest, guitarist Hendrix, through the screaming bravado of his music, belongs to the other side of the love generation coin. Violence is, for him, an integral part of the blues of today, and so he feels free to play the guitar with his teeth, set his instrument on fire, hurl it against an amplifier.

"Our music is getting uglier," he has said, and it rages like an angry torrent, almost overpowering at times because of the amplification. But unlike so many of the loudness-is-synonymous-with-excitement groups, Hendrix's sound is not only highly electrified, but electrifying too.

From out of the musical maelstrom, the howl of the leader's guitar comes leaping like a thing possessed, lashing with the anguish of a stricken giant. In contrast to a fair proportion of rock guitarists, whose lack of an individual conception is shown up by the aimlessness of their playing, Hendrix is in firm control of his direction. In his use of feedback, for example, he stretches the notes over several bars, occasionally accompanying the harmonics emanating from this device with a highly developed melodic line.

He claims to have soaked up influences from "everyone from Buddy Holly to Muddy Waters and through Chuck Berry way back to Eddie Cochrane," and one an hear just about everything from sitarlike riffs to crying delta blues from his screaming strings.

"Cats I like now are Albert King and Elmore James," he said, "but if you try to copy them, want to play something note for note--especially a solo or a certain run that lasts over three seconds--your mind starts wandering. Therefore, you dig them and then do your own thing."

When the thin, stooped, sad-eyed young guitarist came gangling into London in September 1966, he gave the floundering local scene a much-needed injection and with his unkempt mane of busy hair started a fashion unprecedented since the heyday of the Presley sideburn. His hair style had already made him an outcast in Harlem, and when Chas Chandler, former bass guitarist with the Animals, and the group's manager, Mike Jeffery, first heard of him, he had taken refuge from the Uptown jibes in Greenwich Village. As Jimmy James, he was playing with his own combo of two months' standing, the Blue Flame.

"We just didn't feel like trying to get into anything because we weren't ready," recalled Hendrix, (his real name, incidentally), but for the two Britishers, he was saying something.

They foresaw a place for the shy young man with the despair-drenched voice and the reverberating electric guitar on the London scene and persuaded him to try his luck there.

"I said I might as well go because nothing much was happening," recalled the guitarist. "We were making something near $3 a night, and you know we were starving."

Hendrix was born 22 years ago on the wrong side of the tracks in Seattle, Wash. He brought with him to England an aura of mystery concerning his origins and musical experience and a tailor-made line of hard-times-and-poverty stories. His colonial version of how he traded the life of an itinerant guitarist for a place in the Isley Brothers' backing group was widely quoted in the British musical press: "Yeah, I'll gig. May as well, man, sleepin' outside between them tall tenements was hell. Rats runnin' all across your chest, cockroaches stealin' your last candy bar from your very pockets." (On his current U.S. tour, he was given a gala reception in his home town, and presented with the keys to the city by none other than the mayor himself.)

After a spell with the Isleys, the guitarist wandered to Nashville, Tenn., where he joined a package show starring B.B. King, Sam Cooke, Solomon Burke and Chuck Jackson and paid his gigging dues until one day he missed the band bus and found himself stranded in Kansas City, Mo.

"When you're running around starving on the road, you'll play almost anything," and Hendrix ruefully. "I was more or less forced into like a Top 40 bag. Playing the things that I'm doing now would have been very difficult in that area."

In Atlanta, he found a job with the Little Richard tour, and on the West Coast he played with Ike and Tina Turner. Then Richard's show took Hendrix to New York, where he played with people like King Curtis and Joey Dee's Starliters.

"Oh man!" Hendrix exclaimed. "I don't think I could have stood another year of playing behind people. I'm glad Chas rescued me."

The guitarist has the restless nature of the itinerant bluesman. "I get very bored on the road," he admitted, "and I get bored with myself and the music sometimes. I mean, I love blues, but I wouldn't want to play it all night. It's just like although I like Howling Wolf and Otis Rush, there are some blues that just make me sick. I feel nothing from it."

The chance to improvise is, he said, of prime importance in his playing. "I love to listen to organized Top 40 R&B but I'd hate to play it," he said. "I'd hate to be in a limited bag; I'd rather starve."

When the Experience was formed on Oct. 12, 1966, three very different personalities were more or less thrown together. Hendrix was united with rock guitarist Noel Redding, who switched to bass guitar, and the explosive drummer Mitch Mitchell. Said the drummer, a devotee of Elvin Jones, "I wasn't at all interested in blues. I was more interested in a sort of pseudo-jazz thing. Noel was very interested in the rock 'n' roll scene of two or three years ago, and so it could have clashed like mad. Instead, we all threw in our ideas, and now we play individually to make one sound."

The first thing that struck Hendrix on his arrival in Britain was the high quality of many of the local musicians and their awareness of "soul."

"One of the first people I ever heard was Eric Clapton with the Cream," he recalled. "I had a couple of his records, but in person he really knocked me out. I didn't know quite what to think, but I guess that if they can dig a cat like Ray Charles, who's one of the all-time greats when you're talking of soul it isn't too surprising if they come up with that soulful feeling. It just shows that they're listening."

It is obvious from Hendrix's eclectic guitar style that he has not only been influenced by people like Waters, James, King and, in particular, Buddy Guy, but has done a complete turnaround in Britain, listening to the local synthesizers of blues guitar--people like Clapton, Peter Green and Jeff Beck.

"I really don't know about that!" he said, smiling. "I listen to everybody, you know, and a lot of the people now are British. But whatever you do, you have an open mind. You don't necessarily take things, you just listen and accept."

Declared Londoner Mitchell, "I don't think this country has anything to teach Jimi, because basically he hasn't changed since he came over. Maybe his outlook has changed a little bit and he's got more scope, but what he is doing is just an extension of his original ideas."

From his viewpoint, Hendrix said, "When you have people to work with who will work with you, quite naturally, you're going to start moving. If you're really interested and really involved in music, well, then you can be very hungry. The more you contribute, the more you want to make. It makes you hungrier and hungrier, regardless of how many times you eat a day."

Hendrix has slipped fairly easily into the British rock scene, and his attitudes are, at times, surprisingly un-American. Nevertheless, at such times he also seems to be rather uncomfortably straddling the fence between his own blues tradition and the Beatles heritage. It seems safe to assume that had he stayed in the United States, he might have been forced to cut his hair and dress less outrageously than he does in Europe.

As for smashing up instruments on stage, the group has been criticized for following in the path of The Who, the first pop group to introduce auto-destruction to the music. To this, Mitchell has a reply:

"Some nights we can be really bad. If we smash something up then, it's because that instrument, which is something you dearly love, just isn't working that night. It's not responding, and so you want to kill it."

Hendrix further likened the process to the love-hate relationship: "It's just like maybe you feel at times when your girl friend starts messing around. You might feel that you wanted to do that but you couldn't but with music you do, because an instrument can't fight back."

The Experience has an enviable reputation for the comparative ease with which it records, one of its singles having made the grade on the second take, something almost unheard of in contemporary rock. This stems largely from group rapport. Hendrix is such a magnetic figure that the two sidemen are stimulated by him, and they, in turn, free him from the restrictions that less intelligent musicians would impose.

"You've got to be musically one jump ahead to completely interpret what Jimi wants and put yourself into it," Mitchell said. "Certain times you might feel his equal, and then he comes out with something that stimulates your mind quite a bit.

"I don't know if the public realizes this, but we could make a damn sight more money by going out doing one-nighters than by recording. When we record, we pay for the studio ourselves and waste a lot of time finding out the different sounds and things. It's easy to go into a 12-bar nothing and put it on a record, but we spend so many hours trying to get new effects, it should be obvious that we're not trying to con the public."

At a recent rehearsal, where proceedings were held up for a couple of hours, the restless Hendrix sat down at the drum kit and tried his hand with the sticks.

"Gotta keep it moving," he commented. "You don't care what people say so much--you just go on and do what you want to do. You never do it quite--I always try to get better and better--but as long as I'm playing, I don't think I'll ever reach the point where I'm satisfied."

In spite of the fact that Hendrix has no particular wish to be hailed as the new king of the blues, he is a unique contemporary interpreter of the genre and a musician whose impact on various areas of the scene has been considerable. The blues, in spite of the intrinsic resignation of much of its subject matter, has, as a musical form, an enduring optimism.

"The blues will never die," the bluesmen repeat with reassuring regularity, and it's probably true. In their own peculiar ways, people like Hendrix are carrying on the tradition.