In his prime, the astral singer-songwriter Donovan appeared to take a serene view of show business and its cutthroat ways. Not anymore. Nowadays, Donovan would like you to know that he never received proper credit for Flower Power, World Music, New Age Music, the boxed-set album package, using LSD and the lyric "Love, Love, Love" before the Beatles did and playing folk-rock five months before Bob Dylan wielded an electric guitar at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival.

These claims - legitimate, by the way - do not emerge from total oblivion, but it's close. Donovan has spent decades hiding in plain sight. He never entirely stopped performing or recording, but he has not been part of the 1960's-nostalgia boom. Only now, with a memoir, a reissued collection of his music and a big hit ("Catch the Wind") used in a car commercial, has he come back into view.

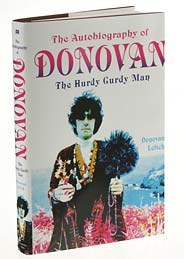

Donovan once wrote a song called "Atlantis" that marveled at a lost world. His own re-emergence prompts similar emotion. "The Autobiography of Donovan" is a very strange book (what else?) that revisits the fertile, trippy 60's, the elaborately constructed aura of Donovan's beatitude, the wild incongruities of that era's popular culture (when the guest list for one Donovan party included Milton Berle, Jimmy Durante and the Doors) and the lingo that has become so quaint. "And, man, I was gratified when the fab chicks screamed," he writes in all seriousness about appearing on his first television show.

The overall language of this book is no less peculiar. It starts in the heavy Scottish dialect of his early years ("I used to sleep wi' ma mammy"). It can take a lofty, didactic tone, even when explicating the effects of marijuana ("Giggles and uncontrolled laughter are often signs of the natural relief that comes from letting go of the conditioning society forces on us"). It adopts the kinds of romantic euphemisms used in his song lyrics; "My Lady of the Lemon Tree" is Donovanese for hostile. And at times it even grasps for the hype that he once disdained. There's something desperate about a memoir that quotes ad copy about its subject's exciting talents.

Bumpy as it is, "The Autobiography of Donovan" is also touching, illuminating and frank. If the author wistfully idealizes his glory days, he can also bring a brass-tacks honesty to describing them. "Yes, I took myself too seriously at times," he writes. "As I say, this was when no one else would." He repeatedly rebuts the complaint that there was anything artificial about either his mien or his music. "I was not invented by a manager," he writes. "I created my own sound and image from the heart and from the start." As with Mr. Dylan's memoir, some of this book's most interesting insights explain the inspiration for extremely well-known music. Donovan writes of wanting to deliver what he calls a Bohemian Manifesto. He also describes the unusual combinations of jazz, classical music, Indian ragas, Caribbean percussion and even heavy metal (those are future members of Led Zeppelin jamming in the midst of "The Hurdy Gurdy Man") that his songs delivered so smoothly.

And he adds his version of what has turned out to be the Rashomon event of his era: the Indian idyll arranged by the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. When he was introduced to the Maharishi, an aide used the phrase "like the Beatles" to describe Donovan. "Well," he writes wryly, "I was flattered to be compared to my friends."

Donovan has indicated that the "The Hurdy Gurdy Man" describes the Maharishi. So why is "The Hurdy Gurdy Man" the subtitle of this book? His autobiography is similarly cavalier about a number of things, not least of them spelling. "Jennifer Juniper," written to woo the sister-in-law of George Harrison, qualifies as one of the most successful musical seductions on record, but Donovan changes the spelling of his own song's title. Mr. Dylan becomes "Bobbie." But he also becomes "the Hebrew shaman with the Celtic name." And Donovan, in gloves-off mode, contends that while Mr. Dylan is the better lyricist, "musically I am more creative and influential."

"The Autobiography of Donovan" stops all too short at the end of the 1960's. But its defining event also occurs then. The book has been built around the author's search for his muse: Linda Lawrence, who met Donovan in 1965, was gun-shy about rock stars (after bearing a child and being abandoned by Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones) and inspired many surprisingly fizzy songs of amorous pursuit. ("Sunshine Superman" is the fizziest of them.) His happily-ever-after finale notes their wedding and progeny but continues to keep the last three-and-a-half decades under wraps.

However time has treated Donovan personally, it has been kind to his music. And the music now gets the jump-start it needs to be enjoyed and admired anew. This book, with legitimate frustration but without hubris, reinstates that music's seminal influence and the underlying seriousness that has always been easy to miss.

"The constant gibes in the British press about my love of beauty has long left a false impression of my work," he maintains. "I was mocked as a simpleton when I sang of birds and bees and flowers like a child." He was also mocked for being wild about saffron, but it turns out that he loves saffron monks' robes and saffron cake with raisins. In any case, this book is where the mockery ends. And the last laugh begins.

Posted November 28, 2005

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário