Ben Harper's command of roundneck and lap-steel guitars—not to mention singing, piano, bass, drums, vibraphone, and production—makes him perhaps the premier roots-rock Renaissance man of Generation X. Here he talks about how he avoids writer's block, how he got the vintage sonic vibe on his latest album, Both Sides of the Gun, and why he feels like a classical musician trapped in a guitarist's body.

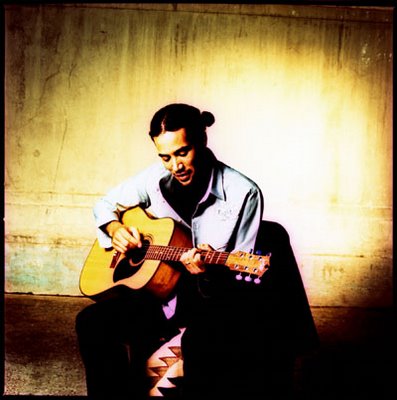

For many of us regular-Joe guitarists, it can be tempting to pessimistically dismiss a guitar-toting rock star whose handsome mug is all over magazine covers and VH1 spots as yet another example of pop culture elevating form over substance, beauty over soul. But if you’ve made that assumption about Ben Harper just because he has graced the cover of Rolling Stone (twice), made a guest appearance on Jack Johnson’s chart-topping soundtrack to Curious George, and received coverage in mainstream media (both CNN and an Australian news magazine were interviewing him on the day of our photo shoot at his family’s Claremont, California, music store), well, you’ve made a huge mistake. Influenced by everyone from Blind Willie Johnson and Mississippi Fred McDowell to Jimi Hendrix, AC/DC, Bob Marley, Cat Stevens, Bob Dylan, and Jerry Douglas, Ben Harper is a prototypical guitar fanatic—which isn’t surprising, considering his upbringing.

Besides spending countless hours as a youth hanging out (and working) in his parents’ shop, Folk Music Center, Harper began attending Taj Mahal concerts at the age of six and learned from both his mother (“an incredible singer and acoustic guitar player”) and legendary multi-instrumentalist David Lindley, with whom Harper’s family has been closely associated as far back as he can remember. Early encounters such as these helped Harper evolve into a roots-rock Renaissance man, with an enviably multifaceted vocal style and an uncanny ability to blend standard six-string and lap-steel guitars into a musical brew that is simultaneously ferocious, funky, and folky.

On this year’s Both Sides of the Gun (Virgin, www.virginrecords.com), Harper’s seventh studio album, he serves up the same vibe fans have come to expect, but with a few new wrinkles. For starters, the album has a soulful depth that surpasses his past efforts. Harper also played drums on all but three of the 18 tracks, a step that he says not only served as a fun diversion but also significantly increased the impact of his guitar parts. And, though the album tracks could have fit on one disc, as producer Harper felt that the record’s stylistic diversity was best served by making Both Sides a double disc—an uncommon move these days.

We spoke with Harper just prior to the release of his new album and the launch of its promotional tour. Despite having just completed a daylong rehearsal, he spoke at great length about his approach to practicing, songwriting, and recording—as well as the orchestral melodies that incessantly play in his head, night and day.

Both Sides of the Gun has an impressive variety of songs, a great soul vibe, and a nice mix of guitar work and instrumentation.

HARPER Thank you. I always had pretty good luck mixing things up on past records, so I figured I could do it again. But as I kept trying to force that mix of songs and moods, I was stumped for the first time. It didn’t feel like a complete body of work until I split it into two discs. I discovered that power of uniformity working with the gospel group Blind Boys of Alabama [on the 2004 collaboration There Will Be a Light]. Even though we kind of pushed the limits of what gospel can mean, the album still had a consistent theme and sound. That inspired me to make this a double album so that there isn’t so much variation within each record.

At what point did you realize you should make two albums?

HARPER After about the 117th track sequence. Once I broke it into two discs, it sequenced itself. Literally, it fell together in minutes.

Were the new songs written recently or have some been around for a while?

HARPER “Black Rain”—which talks about the ultimate representation of administrative irresponsibility and political injustice, in terms of what happened in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina—was written in the studio. We were in the recording process when that all went down. “Please Don’t Talk About Murder While I’m Eating” was written in the studio, too, but the rest were written between the time Diamonds on the Inside [Harper’s 2003 release] was finished and the time we started this album.

How do you deal with writer’s block?

HARPER I don’t mean to boast, but I’ve never had it—let it be known that I’m knocking on wood! Lyrically, I overwrite songs absurdly—I write a chapter for every song. I don’t lift the pen until I get every idea out—good, bad, or indifferent.

What about getting out of musical ruts?

HARPER That’s the great thing about playing slide and roundneck—you’ve always got something to say because of the different approach each one requires. If I get on roundneck and I’m stuttering, I’ll just put the damn thing down and go to slide guitar. That has really kept it fresh for me. No matter what guitar riff you try to cop, it’s always going to sound different on slide guitar.

How many instruments did you play on Both Sides of the Gun?

HARPER Drums—they were my first instrument—guitar, bass, piano, vibraphone, congas, shakers, tabla, and other percussion. I brought in other players when I knew the job was too dangerous—like on “Serve Your Soul,” “Get It Like You Like It,” and “The Way You Found Me.” I could never pull off that kind of drumming. But everything is built around guitar and voice. Guitar points the direction on every song.

What made you decide to play drums for most of this album?

HARPER I played them on “She’s Only Happy in the Sun,” on Diamonds—I played all the other instruments on that record, except for keyboard—and when I was preparing for this record, I knew I wanted to stretch out more on the drums and get more of that feel.

Does laying that foundation help you lock in better when you track the guitars later?

HARPER Definitely. There’s something musically significant when you play the bass, drums, and guitar on a track, because the same idiosyncrasies and accents come out at just about the same time on the different instruments.

You’ve said in the past that you feel like a classical musician trapped in a slide guitar player’s body.

HARPER I hear classical melodies in my head, nonstop, every second of every day.

What instrument do you hear them on?

HARPER Entire orchestras—tympanis, cellos, bassoons. I’m telling you, man. I’m in the wrong field! But when you check out my solos, you can tell that it’s classical music informed by rock. Jimi Hendrix’s longer pieces, like “1983 . . . (A Merman I Should Turn to Be),” clued me into the fact that rock and classical music can be connected. I’m not schooled in music theory, but I know what sounds I want and I know how to get them.

Have you considered using guitar synths to get those sounds in your head?

HARPER No. I enjoy mixing in Mellotrons, synths, and other electronic voices, but guitar is just too great an instrument. It’s a perfect invention, and there’s nothing else that can say what it says in the way that it does. If I’m proud of anything on this record, it’s that none of those other instruments have overshadowed the guitar.

Was “The Way That You Found Me”—which has a swinging piano and upright-bass groove—written on guitar, too?

HARPER Yeah, that was written as an acoustic- slide piece, but then it was kind of overtaken by the other instruments. Michael Ward from the Wallflowers is playing a Martin 000-18 in the background, but it’s hard to hear because we tracked in the same room as the other instruments and it kind of got swallowed up. I played the solo and outro on my Asher lap-steel—which has a chambered mahogany body with a maple cap that gives it an acoustic resonance, even though it’s a solid-wood guitar compared to, say, a Weissenborn. I’d been listening to a lot of Howlin’ Wolf, John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, and Mississippi Fred McDowell, and I noticed that those guys got the most acoustic-like electrified sound I’ve ever heard because the mics were so far away from their amps. That yields a breathier sound and more room ambience. I was going for that tone and I researched quite a bit before this record to find out how they got it.

Do you feel like your guitar playing has evolved since Diamonds?

HARPER It’s getting a bit raunchier—acceptably raunchier—and more aggressive and melodically purposeful. There’s more letting go and shedding of inhibitions.

Mentally, or in the sense that you’re a more proficient player now?

HARPER A combination of those. When you surround yourself with great players, five percent will make you say, “I should never pick this thing up again.” But the other 95 percent will inspire you to play something you never would have otherwise.

Do you practice guitar?

HARPER Not as much as I should, but more than a lot of people I know. But playing is not practicing. Practicing is taking something you can’t do and trying it until you can. I do that once a week—often enough to be able to keep throwing different things into my playing, especially on slide. I’ll put on a Jerry Douglas record and get real pissed off. These days I never learn anything note-for-note, but I’ll get the vibe of licks and learn new tunings and chord progressions.

What first made you realize you could really go somewhere with it?

HARPER When I finally learned how to double thumb and fingerpick Mississippi John Hurt’s “Hey, Baby, Right Away.” I learned it note-for-note. Once I did that, I was, like, “I’m doing this for the rest of my life!”

How did you discover that technique?

HARPER I’d heard that song all my life, but the technique, John’s voice, the tempo, and the spirit in the song completely penetrated my soul when I was 15 or 16. The three keys to my guitar playing were Mississippi John Hurt’s fingerpicking, Weissenborn guitars—because they let me get a wood-body tone while playing lap-steel—and Jimi Hendrix.

Before you found those keys, what had you been working on?

HARPER I was playing flattop and Hawaiian and blues music on lap-steel. Tampa Red songs translated well to lap-steel, and I loved Black Ace, who played a National Tricone squareneck, and Blind Willie Johnson. I was focusing on their work, but I didn’t have the double thumbing down, and I didn’t realize that that was such a crucial part of fingerpicking blues—bouncing with your thumb and picking with your fingers simultaneously.

Are there any other insights you wish someone had shared with you as a beginner?

HARPER That’s a good question. Each person has to live it and define it with their own life. I could’ve taken lessons and learned to sight-read and pick apart blues songs note-for-note instead of by instinct, but that would’ve taken me down a different path. And there’s no other path I’d rather be on. If I had sat down with a metronome when I was 14, I’d probably be more on with my timing now, but then I wouldn’t come up with the crazy, loose, off-kilter stuff that I love the most.

The “right” way is the way that gets you where you know you’re bound. If you want to go to music institute, hell, you may come out of there an incredible player. Jeff Buckley went to Musicians Institute, and he had some of the most interesting chords and chord progressions of my generation. So there is no wrong way, as long as you get there. I love being me and doing what I do the way I do it. Would I like to be able to read music? Yes! Would I like to be closer to my inner classical musician? Of course. I could’ve done stuff differently—but then, chances are I’d be somewhere different, missing what I have now.

RECORDING BOTH SIDES: MODERN TOOLS, VINTAGE SOUND

One of the most surprising things about Ben Harper’s latest album, Both Sides of the Gun, isn’t that its production sensibilities are old-school—all of Harper’s albums have a warm, vintage feel—but rather how he got that vibe this time around. Previously, he swore by ’70s-era studio gear, including reel-to-reel multitrack tape machines and solid-state mixing consoles. But for these sessions he used a state-of-the-art Pro Tools hard-disk system.

“I was an all-analog guy until the Blind Boys record [2004’s There Will Be a Light],” Harper admits. “That’s when I put the sonics under the microscope and said, ‘OK, I wanna hear the difference. And if I can’t tell the difference, I’m moving forward with the method that helps the process move along the smoothest.’ We recorded the first few songs on both analog and Pro Tools setups, but I wasn’t hearing or feeling a difference.” He switched to ProTools, but with the additional “padding” (as he calls it) of a Neve board, Neve preamps, and vintage mics. “That’s really where you get the warm sound,” he points out. “Not to say that you can’t do incredible stuff with Shure mics and Pro Tools in your bedroom—because you can, and I’ve heard it. There are kids in their garages making unbelievable songs straight into Pro Tools or GarageBand.”

With instruments, Harper still leans retro—and he often routes his acoustic guitars through electric-guitar stompboxes and amps. “Guitar-wise, the whole record was definitely defined by an early-’50s Gibson J-50 and a new Martin HD-28VE,” he says. To capture amplified-acoustic tones to disk, Harper explains, “We experimented with each instrument and amp, but the mics were always between a foot and six feet away from the amp. We’d also switch on the overhead drum mics, which were in the same room, to hear the guitar through those. We’d end up using either that or a combination of that and the amp mic.”

For traditional acoustic parts, it was even simpler. “We just used one mic and found the sweet spot. We mostly used vintage Neumanns—a U 67, a KM 54, a U 47, and a U 48,” Harper says. “I know there are a lot of miking techniques, like crisscrossed stereo mics, and stuff like that, but we just stuck a big ol’ tube mic in front of it— right around the 12th fret/soundhole area—and went for it.”

During the sessions Harper also discovered one of his favorite new guitar-tone recipes. “I played a Fender Custom Shop Telecaster on ‘Please Don’t Talk About Murder While I’m Eating,’ but it’s sort of a clean, Johnny Cash–style part,” he says. “That showed me how amazing a clean Telecaster through, say, a Fender tweed Deluxe accents an acoustic guitar when they’re stereo-panned.”

Perhaps the best example of Harper’s blending of influences and instruments is the song “Engraved Invitation,” which features straight-ahead flattop work, distorted guitar, weird guitar stabs, and a crazy solo. “That song pulled to go in so many directions, and it was a challenge to find the right balance of acoustic and electric,” Harper notes. “I just stacked guitar parts, played drums and bass, and let it be as raggedy and loose—but musical—as possible. At first it was really AC/DC-ish. Finally I stripped down the electrics to just one track of a 1956 Gibson Les Paul Special, soft-panned left, and the J-50 acoustic, soft-panned right. Then there’s a bunch of noodling on the Asher lap-steel, through a Dumble combo amp. I turned the back pickup off and stuttered between the two pickups with the selector switch.”

WHAT BEN HARPER PLAYS

• Acoustic Guitars: Weissenborn Teardrop (circa 1930s) and two Style 4 (1925 and 1927) lap-style guitars; a 2004 and a custom 2005 National Reso-Phonic Model D Western squareneck; 2005 Martin HD-28VE; vintage Gibson J-50; 2005 Cole Clark dreadnought.

• Electric Guitars: Asher Ben Harper lap-steel; 1956 Gibson Les Paul Special; Fender Custom Shop Telecaster.

• Amplification: Seymour Duncan Mag Mics (Weissenborns); National/Lace Humbucker (Nationals); Fishman Ellipse System (Martin); Trance Audio Amulet system (Gibson); Cole Clark Dual Input Acoustic Pickup (FL2); Radial JDI direct box; Dumble Overdrive Special amps—one 1980s 100-watt 1x12 combo and a 1970s 50-watt head driving a 2x12 Dumble cab.

• Effects: Ernie Ball volume pedal; Vox V847 wah; Teese RMC wah; Ibanez TS808 Tube Screamer; Ibanez AD99 Analog Delay; Electro-Harmonix Small Stone phaser, Demeter Tremulator; Line 6 DL4.

• Strings: D’Addario EJ16, EJ17, EJ18, and EJ22 sets for slide guitars; D’Addario EFT16 sets for Cole Clark, Gibson, and Martin acoustics; D’Addario EXL110W sets for Les Paul and Telecaster.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário