AN hour before Arlo Guthrie is to go on stage, a reminder of life's serendipity walks into the old church here.

A volunteer doesn't recognize the man at the door, and she can't find his name on the "comp" list of invited guests, either, so she calls over Guthrie's longtime right hand, George Laye, and tells him, "There's a Mr. Wilcox…."

Laye confers briefly with Richard B. Wilcox, laughs and says, "Oh, of course. I'm sorry. Go right in." Then as soon as the new arrival has stepped into the onetime sanctuary to await the concert, Laye announces, "That's the chief of police of Stockbridge!"

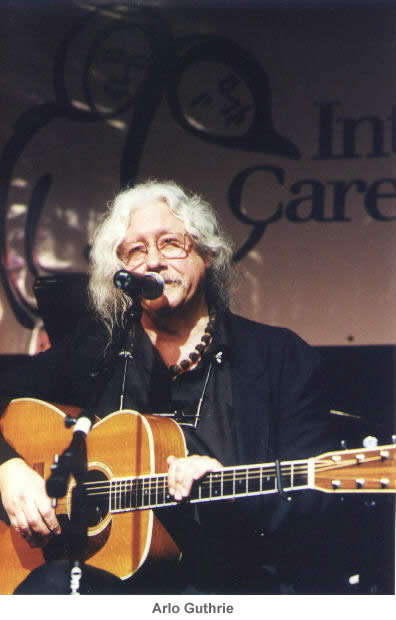

Everybody has a good laugh at that, for this church in the Berkshires would not be the Guthrie Center today had it not been for Stockbridge police. And Arlo himself … well, had not those cops arrested him four decades ago for the crime that began right on this spot, he might have gone on to be a forest ranger, as he'd intended as a kid, and not followed his doomed father, Woody, into musical storytelling.

The tale of that absurd life-changing encounter became the entire A-side of his debut album, "Alice's Restaurant," the 18-minute, 20-second song relating how, as a teenager in 1965, he had Thanksgiving dinner in the church — then a commune of sorts presided over by Ray and Alice Brock — and thought he'd do a good deed by carting away the truckload of trash that had accumulated at the place … except the dump was closed on the holiday, so he tossed the stuff down a hillside, where the cops found it and took their "27 8-by-10 color glossy photographs" of the scene and threw his young butt in the slammer.

The catch was, all those glossies were of little use as evidence when his case came before the local judge — the blind judge — and then came the real twist, in Arlo's song's version of history, when the misdemeanor arrest prompted a New York draft board to toss him aside with the other rejects, the mother stabbers and father rapists, thus sparing him a trip to the front lines of the Vietnam War or, more likely, flight to Canada.

"Garbage has been very good to me," sums up Arlo Guthrie, who was resting up, that hour before his "Spring Revival" concert, in the old bell tower of the church, now the green room lounge of his nonprofit Guthrie Center.

FOR years he owned a farmhouse a half-hour away, in a hill town with no traffic light, but he did not get the church until 1991, when he was brought here by a TV crew filming what he calls a "whatever-happened-to-him?" feature. The deconsecrated church, which dates to 1829, had been through a number of owners since the Brocks had it and was not in the best shape. But the owners at the time must have seen him coming, for that story has them peering out the window exulting, "Oh, there's Arlo Guthrie, he'll buy it," and he did, with the help of donors, whose names now adorn a wall of the Guthrie Center.

FOR years he owned a farmhouse a half-hour away, in a hill town with no traffic light, but he did not get the church until 1991, when he was brought here by a TV crew filming what he calls a "whatever-happened-to-him?" feature. The deconsecrated church, which dates to 1829, had been through a number of owners since the Brocks had it and was not in the best shape. But the owners at the time must have seen him coming, for that story has them peering out the window exulting, "Oh, there's Arlo Guthrie, he'll buy it," and he did, with the help of donors, whose names now adorn a wall of the Guthrie Center.Today, there's still no heat or air conditioning in most of the structure, but that doesn't stop the crews of volunteers and one paid staffer, the 64-year-old Laye, from offering free community lunches every Wednesday, with health food (lentil soup, rice dishes) provided by a nearby yoga center. Thursdays there's "Hootenanny Nite!" with an open mike for local musicians in the 100-seat performing space that has tables set up nightclub style where the pews once were. Summer weekends, the professional acts take over in a "Troubadour Series." And on two or three weekends a year it's all Arlo, in fundraising concerts that help keep the operation afloat.

His annual spring weekend has spawned another tradition, a "Historic Garbage Trail" walk to combat Huntington's disease, the hereditary neurological ailment that killed his father. Participants trek 6.3 miles from the church to Stockbridge, the scene of other "Alice's Restaurant Massacree" landmarks, the tiny restaurant once run by Alice and the Stockbridge police headquarters. The cops no longer have cells there ("liability issues," Chief Wilcox says), but the front of one has been preserved for posterity and was displayed on a platform for this year's Sunday hike, May 21, so the walkers could pose behind the same bars that once confined the littering Arlo. In the spirit of the '60s, they also were given pens embossed "This pen has been stolen From Stockbridge Police Department," courtesy of the chief.

As a child, the 57-year-old Wilcox was a model for a Boy Scout painting by the local chronicler of Americana, Norman Rockwell, and he later served two tours in Vietnam. But the chief long ago came to embrace Arlo and that contentious era as slices of Americana as well, even if a church volunteer did almost diss him and his wife at the door that evening. "They try to keep the riffraff out," Wilcox reasoned, "but we snuck in."

The Garbage Trail walk alone brought in $8,500, but the weekend was more than a fundraiser for Arlo, who took the revival theme seriously, for the time back home was his bridge between two long forays on the road: The one just finished was a 40th anniversary tour commemorating the Alice's Restaurant incident, an occasion to dust off the rambling story-song he normally eschews these days; the one upcoming is a "Guthrie Family Legacy Tour," which was to begin in Alaska, of all places, and which takes him to downtown Los Angeles on Saturday for a free 3 p.m. concert at California Plaza, part of the Grand Performances series there.

The "Legacy Tour" looks to the past too, obviously, embracing the work of Arlo's father, the voice of the Dust Bowl Okies and other underdogs, who penned "This Land Is Your Land" as a response to Irving Berlin's "God Bless America." But it's also a showcase for new songs written from lyrics Woody Guthrie left behind — and for newer musical Guthries, who are in no short supply, thanks to Arlo. The bushy-haired hippie kid of the Woodstock Festival is now, at 58, a father of four and grandfather of five.

THREE generations of Guthries are milling about the church bell tower on this Sunday night. As Arlo himself relaxes on one sofa, a harmonica ready around his neck, his youngest daughter, Sarah Lee, 27, plops in the sofa across from him, cradling her own little girl, Olivia, who is not quite 4. Between them, a small table supports three lighted candles, while another to the side displays a drawing of St. Francis, a small skull ("to point out that the body is fleeting but the soul is forever") and a bottle of sacred oil given to Arlo by his spiritual advisor Ma Jaya, a onetime Brooklyn housewife (Joyce Green Difiore Cho) who now heads an ashram in Florida.

THREE generations of Guthries are milling about the church bell tower on this Sunday night. As Arlo himself relaxes on one sofa, a harmonica ready around his neck, his youngest daughter, Sarah Lee, 27, plops in the sofa across from him, cradling her own little girl, Olivia, who is not quite 4. Between them, a small table supports three lighted candles, while another to the side displays a drawing of St. Francis, a small skull ("to point out that the body is fleeting but the soul is forever") and a bottle of sacred oil given to Arlo by his spiritual advisor Ma Jaya, a onetime Brooklyn housewife (Joyce Green Difiore Cho) who now heads an ashram in Florida.Ma also provided the interfaith dedication that hangs over the entrance to Guthrie Center's main room: "One God, Many Forms/One River, Many Streams/One People, Many Faces/One Mother, Many Children," and above her words is a portrait of a somber Woody Guthrie with his guitar, pointing into space. Someone has made sure the message does not seem too heavy, however, by adding a cartoon-style balloon that has Woody saying, "He went that way…."

There's another portrait of Woody in the bell tower lounge, beside one of Jesus. All faiths get equal billing here, even as Arlo says, "I'm still a Jewish kid from Brooklyn."

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário