"There's so much information in the songs and the lyrics that it felt like one more title was almost pretentious," says Pearl Jam's Eddie Vedder. That's just one explanation for why the band's eighth studio album is simply called Pearl Jam. Another would be that it is the group's most democratic effort since its massive 1991 debut, Ten. On songs like the laid-back acoustic beauty "Parachutes" (music written by Stone Gossard), the eight-minute trip "Inside Job" (lyrics by Mike McCready) and the first single, "World Wide Suicide" (which is killing at radio), PJ brought a live feel to the studio, laying down tracks that showcase tasty guitar interplay and a heavy backbeat. "When you collaborate, you still have this urge to stay in the studio after everybody's left and do things the way you want to," says a chilled-out Vedder on a cold, dark day in Seattle. "But you can't do that."

What was your first musical memory as a kid?

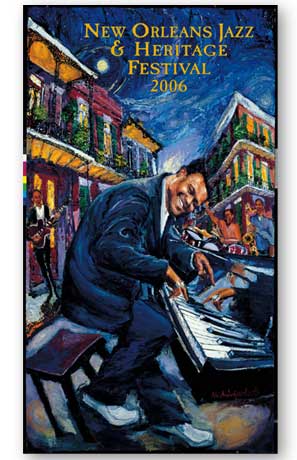

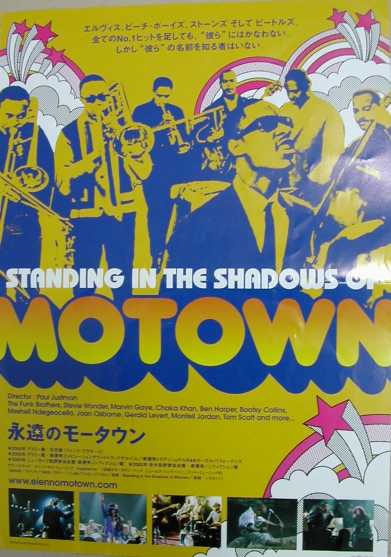

There was a group home of sorts in Chicago, and they had a turntable in the basement. Because it was kids without parents there was a large range of ages, and some of the older kids had more mature tastes. So I was listening to Jackson 5; they were listening to James Brown and Sly Stone. I remember everything on the Motown label seemed to be great. Little basement, that's what I remember. I can still smell it, too.

What did it smell like?

Like a basement in Chicago. Dank. One of those basements that never gets dry. And maybe some Afro-Sheen that some of the kids -- a kid called Maurice -- had in his hair. I think it was called the Lake Home for Boys. It was just on the wrong side of the tracks. The tracks were right there, we were just on the wrong side.

Speaking of smells and stuff like that, what does Pearl Jam taste like?

I don't . . . uhhh . . . I have no idea. That's like saying, What does Pink Floyd taste like?

No, no, no, dude. I mean your grandma Pearl's jam.

I never had it. It was apparently a recipe that was handed down. It's mythological now. I never saw the recipe, I just kind of heard about it.

What was it?

I imagine it was regular preserves with a bit of mushrooms in it . . . a peyote kind of deal. It's the whole Mary Poppins theory of tripping out -- a spoonful of sugar makes the medicine go down. It's so typical that an American woman in love with an Indian has to add sugar to something to keep herself totally culturally intact.

So did you have a piano growing up in your house in San Diego?

Well, my brother got the guitar and we got a stand-up piano, and then I got a Les Paul copy guitar. He excelled immediately. He was playing blindfolded, and I still couldn't get my fingers to push down a chord. I was very disturbed by that. It took about a year, and then one day, all of a sudden, it felt like a friend. I'll never forget it.

Was there a moment?

Yeah. It was "Cat Scratch Fever." All of a sudden, the guitar felt right underneath my hands. My hands had finally gotten strong enough.

What were the circumstances of you getting the guitar?

My birthday was on December 23rd, and the one time I used it to my advantage was to beg and plead to put the two presents together to afford the $100 guitar. And it worked.

Was it from a Sears catalog?

No, I remember it was a Memphis Les Paul copy. It kind of looked like the guitar that Ace [Frehley] really played.

That's what you were going for, I'm sure.

It's interesting, because I had only had a few lessons. The guy was great, his name was Bud Whitcomb, and I'd do weeding in his backyard to get a few free lessons here and there. At the time he was teaching me bar chords, he wouldn't let me do anything but bar chords, and I hated him for it. It was a lot to ask twelve-year-old hands to do at that point, it was very frustrating. He went on vacation, and I went to church and they had this little booklet of songs that had little charts with open chords in it. And I stole it!

Oh man!

They had a lot of them. They were hymnals, there were a lot. It had songs like "Black and White." So he left, he went on vacation and I learned these open chords and all of a sudden these open chords made me feel like writing. Early on, I didn't see becoming a lead player. I just wanted to write, I just wanted to have patterns that I could write on top of. So once I got those open chords, I started writing pretty quick.

Since I've always had so much respect for your songwriting, I want to know what is the deal with the instrumentation in the band. Only recently, you've added B3 keyboard stuff. Why have you never used horns, or strings, or girls?

I think we're always trying to find new ways to play within the group. I know that Stone Gossard just picks up the guitar and refuses to play something he's played before. It can be frustrating to collaborate with him, because he wants to do something different at all times. I think that the band is made up of a certain number of colors, and we need to see how many variations we can come up with. The keyboards come up in some of the records. "Black" might even have some piano on it, but it felt like that was the next shade to add. Horns and strings and background singers are things I might reserve the right to do in the future. But we're still plugging away with the ingredients we have and trying to be as progressive with our thinking within those boundaries. Do you hear room for horns?

Perhaps. I was just wondering if you had ruled it out?

I think you go into a record thinking that you can try anything, and that you will. That's before the sessions over; by the end, even when you take a long time, it's time to finish and you're working with what you got. Just like making film clips or arrangements, working with horns and stuff is just time consuming stuff. And I think, we've used up all our time on the clock working within our own groove. The communication in our own group is fairly exhaustive, at least with songs.

Jeff [Ament] had mentioned that you guys were thinking of doing a video for this record?

I think it's a great art form if it's approached the right way. But it's time consuming...just like interviews! [laughs] It seems like the time spent playing live and organizing shows, and putting the record and the artwork together seems to take up all the time we have. Until we can do it right...we'll see. I found a guy I'd like to do it with, but we'll see.

Is it a secret who that is?

A young guy called Fernando Apagapa who's an artist. He's all-around, refuses to be pigeonholed, works with every medium there is. Line drawings with hair to stitching up leather bodices . . . everything is very organic. I think the only reason he hasn't made a name for himself in the art world is that he holds the art world in contention. I've talked to him and I think the fact he has a high respect for us is a high complement.

Do you have a favorite obscure Dylan song?

He did a record of covers.

Good As I Been to You!

Yeah. They're not his songs, but I was listening to that record on a tape recorder that had only one speaker working. A tiny, little thing . . . and it worked so well with the music -- it sounded like a Bessie Smith or Robert Johnson record. I just can't think of the names.

"Frankie and Albert" . . . "Jim Jones" . . . "Sittin' on Top of the World" . . .

That's it. "Sittin' on Top of the World."

Also, at that Nader benefit in 2000, you came out and you did "The Times, They Are A-Changin'" and you said you had permission from the author. How did that channel open up to you? Was it at his thirtieth anniversary at Madison Square Garden?

After that show at the Garden, everyone congregated in a corner of this Irish Bar in New York that's no longer there. I tried to find it, and it's gone. Some real history took place that night at the table. The oldest Clancy brother was reciting these long Irish poems about war, and they were eight minutes long, and he knew every word. Then a guitar came out, and it was getting passed around. Ronnie Wood was there with George Harrison. It was a great night. When I went up to introduce Chrissie Hynde, which I was there to do, for some reason this really large guy who looked like he walked out a Spiderman cartoon -concrete-bald head and shoulders like a shipping crate -- he lifted me off my feet by this ski jacket I had. He said, "You don't belong here." That was still at the beginning of our recording career, so I couldn't really argue that fact with him! I was like, "Alright, my friend!" I was standing next to Willie Nelson's guitar. Someone saw him dragging me off the stage, and they stopped him just before I had to go on. Later on that night, he turned out to be a great English guy. We were good friends by four in the morning -- he was Bob's security guy.

We were about to record our second record, and Bob passed on a few lessons to me in the corner, one of which was, "Don't read anything in the paper. Don't watch TV. Get away." I felt that same thing at the time, overly inundated and somewhat like a commodity -- you'd watch TV or open the paper and our band was there as some kind of commodity. Our band had become part of the pollution.

You bootlegged concerts growing up. Still have the tapes?

I've still got them. I listened to them a lot. In a way, music for me was fucking heroin. It was something I needed. And to see a live show was something I needed, it gave me strength through adolescence and through this young adult life -- to feel like there was a purpose to get through this whole thing. After a live show, the high could wear off in a day or two. The bootleg recordings and listening back at them with your eyes closed and headphones seemed to make a crappy recording actually sound pretty good. It was like getting high again. I was a user.

Was there one you played a lot?

An earlier X show I listened to an infinite number of times. The early Who shows, at Golden Hall. The Pretenders. Bands like the Tubes. I'd record everybody but there are certainly ones that lasted forever.

Where'd you position the recorder?

It depends what kind of machine. A lot of them were early Walkmans. I had a CostClub-ten-percent deal. This was when they first came out, the first stereo recorders, so they were rather cumbersome compared to a whatchamacallit -- an iPod. You'd have to hold the whole cassette player up, but 4 or 5 years later you could plug a mic in and sneak it on your lapel. For every good bootleg I got, I probably got caught half the other times, because I was usually close to the stage. That's why I just wanted people to record a show and not be hassled by The Man.

So you got kicked out?

They'd take my recorder and rough me up. A lot of times, they'd take the tapes, which is a little nicer. Some guys were overly aggressive. I never once sold a tape. On very few occasions, if someone was very into it, I'd make them a copy.

Is there any comparison between surfing and crowd surfing?

The crowds are much more dangerous, because of the germs and bacteria in a sweaty mosh pit circa 1992. Now that the ocean has become fairly polluted, they might be about even.

As far as the feeling?

It's hard to get momentum standing up in a crowd, because people grab your shows. That's one of the exciting things about a wave-you're standing up and you have real good peripheral vision. There's something about surfing...these waves come from 2,000 miles away sometimes. These swells, they crack in a kind of firework, and you ride the firework and give it meaning and you're connected to nature. It's like no other thing I've felt except for maybe music. And holding your newborn.

How much fun did you have getting onstage with the Kings of Leon?

It's a great record, and the song "Slow Night, So Long" -- I had disappeared onto some little island to write and surf and the only record I had besides the Pearl Jam stuff I was working on was that [Aha Shake Heartbreak]. I played it for some of the locals, who didn't know anything outside of their local traditional music, and they had such strong positive reactions to the record. It was a clean slate to bounce it off of. I was excited, and when they opened up for U2 -- I hadn't met them, but I wanted to tell them that story -- that their record transmits really well to unbiased ears. We started hanging out, and the second night we bashed some tambourines and it felt exciting.

Are they the cream of the crop as far as younger bands?

They certainly hit a reflex in me, and the new Strokes record is just a great piece of work. The sounds, and his vocal delivery is really great. Both those guys...

Caleb and Julian.

Yea, Caleb's vocal delivery is so unique and his phrasing; it's like what they used to say about Sinatra -- his phrasing is what really made it. I'm not into Sinatra, but I get that. George Jones is another thing, and even McCartney and Lennon. You listen to these songs, but it's unconscious the way they phrase things. Joey Ramone as well.

What kind of wine do you like onstage? As long as it's red?

As long as it's red and there's a spare in the back. There's this homemade stuff some friends have been making for me for the past few years, and I can't do without it now.

What kind of grapes?

I can't tell you; there's a bit of variation there. On the first leg of our last tour, I had been drinking regular wine, but I got the good stuff for our last show, and I don't know what kind of grapes they are but it's twice as potent. I realized this about halfway through the show. It was a political fundraiser, so I was like, "Damn I really gotta sober up!"

Why do you think the musical community has been so quiet recently about the war, about the president? Or maybe you don't think that?

I'm not sure what's out there. People like Steve Earle are a great example. He goes on Bill O'Reilly. It's beyond commendable. It's gutsy and I think a lot of it, it doesn't get heard. Or maybe people don't like to mess up a good time. I mean, we could talk about it in this interview, and it might not be the part that gets in. We could talk about Democrats and why they aren't leading an anti-war movement, are they waiting for a shift in the polls? We could talk about our country in ways outside the war, like why they refused to sign the Kyoto Protocol, in regard to environment. Why aren't we agreeing to strengthen the conventions on biological weapons? Why haven't we signed the ban on landmines? Why haven't we banned the use of napalm? They refuse to be subject to the jurisdictions of the International Criminal Court. They can get away with anything. If you highlighted the classic aspects of this war, find out who's fighting and who's dying, and why are there billions of dollars being spent on this war and schools are crumbling and 45 million people in the US don't have health insurance? This is all stuff I've been reading in a book on Iraq called The Logic of Withdrawal by Anthony Arnove. It seems like it's a class issue, because there are things going on underneath this spectacle of war, and the Bush administration is using it as a distraction for the ills of this country that are being not only ignored but exacerbated. But, is anybody else saying that in interviews, and are they being edited? I'm not sure. Right now, we are in a situation where the "Worldwide Suicide" song is getting airplay, and three years ago that might not have happened. After 9/11, they took "Imagine" off the air! It's interesting...I'm not sure why.

Do you have a favorite self-titled record out there?

Ha ha. The first 3 Zeppelin records were untitled. Those are great.

Cool. But, your self-titling was the biggest group effort as a record.

It was meant to be. It was similar to how the first ones were: absolute democracy. When you collaborate, you still have this urge to stay in the studio after everyone's left and do it the way you want to. But you can't do that. Going back to what we were talking about, the Bush administration, they think they're making a solo record, leading our government and representing us to the rest of the world. And they're not allowed to do that, it's actually criminal.

They're the new Presidents of the United States of America.

Yeah! Where no one else is allowed to contribute. You had 15 million people in February 2003 come out to the largest global protest that the world has ever seen and they were treated as a special interest group. That's the lack of respect we have to fight against. Going back to the record, in a way it feels like our first record, and also there's so much information in the songs and the lyrics and it felt like one more title to sum it up was almost pretentious.

Do you feel better listening back at this album more than the others?

There's a grace period after you make a record, and you know what went into all the songs. And I don't think we've ever made a record where it didn't feel like our first record. Looking back, you can say, "that record is a little mid tempo" or "why was that the single?" I can't necessarily answer objectively, but I think, melodically speaking, the songs are pretty strong. I think the drumming on it is impeccable. Some of the players in the band like Mike and Matt, we figured out a way to create space for them to get to that level of energy that they have when we play live. I'm not sure how that happened -- it could have been released even more, but I think it's a step in the right direction.

Were you ever secretly pissed about Billy Ray Cyrus' Achy Breaky Heart keeping Ten out of the Number One spot?

No. I never even realized that. I'm sure there were other things to worry about at the time. I might even have been thankful that it wasn't Number One. I might reject the idea now. I'm mature enough to handle it, but at the time I couldn't handle it.

What do you remember about your first gig, as Mookie Blaylock?

The very first show we played was after my first trip to Seattle. On the 6th day we played a show, and on the 7th day we recorded. I know we were supposed to rest, but we recorded. What I remember is the sound check, because we were opening for two other bands on the bill, and they opened the doors during sound check, and I had my eyes closed and it was an empty club -- called the Off Ramp -- and I opened my eyes for the last chorus and the place was full. I had played for a number of bands, but I never played for a full house before. It's a good analogy, it happened kind of quick for us.

Do you remember who headlined?

No. No idea.

What's the most amazing thing you've seen from the stage?

I probably have an answer for each tour, if not each show. I remember a gig in Florida, it was a big baseball stadium, maybe towards the end of our second album tour. You always saw people get passed around the pit, it was the Norelco Razor with three pits going in the middle of one mass. That was the beginning of my lifeguard career -- I never felt like I looked up past the front, I was memorizing the faces and making sure you didn't lose anybody. I remember this wheelchair was being carried to the front. We got him up onstage...

There was somebody in it?!

Yeah. We got him up onstage during "Rockin' in the Free World." And I heard last year that that was one of the guys in the movie Murderball.

No way!

I feel like I have a Polaroid of him in my archives somewhere.

What was the first record you bought?

I remember how much it cost -- $5. It was probably a Jackson 5 record. It might have been Got To Be There -- the Michael Jackson solo record...at like a liquor store.

In Illinois?

Yeah, in Chicago.

What about the last?

The Joe Strummer and the 101ers -- his early stuff. I got a batch though. I got the new Crosby record, which is genius. I bought another copy of the Evens record for my friend. When I finally get down to the store, I buy a lot. They know me down there. It's called Easy Street, which we played recently.

You played a benefit there, right?

All the independent record store owners were in town in Seattle, of which the owner of Easy Street is part of that organization. So we thought it would make him look good and he'd be proud if we played his shop.

Do you get ten percent off now?

He sent me a gift certificate, which I still haven't used. I feel like I need to be paying for music.

What about the record you've spun the most times or listened to the most?

It would've been a Who record until I discovered Fugazi, and now they've caught up. All the time through my adolescence I spun Who records, but Fugazi caught up.

Which one? 13 Songs, Steady Diet...?

13 Songs. But I think of their whole body of work as one record.

You've seen the documentary?

Instrument. Yeah.

Isn't it great?

If you go see the Evens play, it's one of the highest examples I can think of. Of course, Neil Young does it, and Pete Townsend does it, but the level of communication that takes place and the amount of respect Ian has for his audience -- even the guaranteed four knuckleheads in the audience. He really cares for their opinion. And at this point, he's mixing himself from the stage -- there's no house mixing guy. He and this woman, Amy, do it from the stage as a two-piece and it sounds full. And he asks, "Should the vocals be louder?" and he turns it up! The amount of communication that takes place...it's certainly not fucking Storytellers or something, but it's a reminder of how powerful the stage is and what responsibility comes with the mic. And this is from a guy who is a punk rock legend. It's evolved into a different form of communication, which is as deep as anything I've ever seen.

Cool. You mentioned Neil Young, have you played with his model trains?

Yes.

Is that exciting?

That's Neil's private thing, I'm not going to say anything about it.

What's the best song you've ever written?

Matt Cameron thought that "Thumbing My Way" was the nicest chord progression I had ever devised.

What about you personally, and lyrically?

I have a few on ukulele that I like. For me, I judge it by melodic substance these days. It's something Johnny Ramone drilled in my head. I think it's where we came from with the first few records, you took a piece of music and added your throat to be part of the noise-if there was any melody there, it was unconscious.

A song like "Black", for instance?

I imagine that has some melody to it. I think being conscious about it, really focusing to make something beautiful...there's a difference between a song and music. I think it's the melodic structure. I think the songs that connect are the melodic ones, they are the really musical ones. I haven't figured the theory out yet, but there's a difference and music is the goal.

Was there something unique about the "elderlywomanbehindacounter" song?

I remember it only because it was so quick. We were recording the second record, and we stayed in this house in San Francisco, and I was outside the house in my own world and the little outhouse had a small room. I'm talking the size of a bathroom, I was able to fit a Shure Vocal Master, which is a 1960's PA, and two big towers of PA and a little amp and a 4 track. I slept in there too. I remember waking up one morning and playing pretty normal chords that sounded good, and I put on the vocal master to hear myself and it came out right quick. I don't even think I scribbled the lyrics down. It took 20 minutes. Stone was sitting outside reading the paper, and he was like "I really like that." So we recorded it that day.

Did it spring from a dream?

It's funny you say that, because in my head I was going back to where I lived in San Diego but picturing myself older. Exactly right. It was bizarre...I forgot that.

For some reason, right now, I'm thinking it's the greatest Pearl Jam song ever.

The thing is, the dream was still alive...sorry. I had just woken up and started playing it, so the content was still in my brain.

Jack Johnson's dad told me some story of you almost dying on some outrigger adventure?

At no point did I think we were going to die while it was happening. About 2 weeks later I took a boat out to the scene of the crime, quite a ways off shore with some pretty heavy current, and the swells were pretty big and we got knocked off a sailing canoe, and it was only then, seeing where we were and the conditions, that I felt the need to vomit. Survival instincts kicked in, though, and I knew we might be out in the water for maybe 8 hours, but I knew for sure we'd get in. I might have been wrong, because the currents were going one way and the wind another. I didn't know that at the time, so instead of hitting the spot in the island where it juts out with a little port there, we were probably headed to Tahiti. After what seemed like a pretty long spell, the sole fishing boat in the water that day-a guy and his 8-year-old daughter were out, and she saw us waving paddles. She couldn't have seen our heads, they were like coconuts. It was a good night on land that night.

You tied one on?

It was interesting hearing everyone's experience. We went around the campfire and talked about what everyone was thinking. And the two girls I was with in the water, they said they actually saw the headline in their minds...

Right? On MTV. "Eddie Vedder and two others die in canoe!"

What's-his-name dies with...

Yeah! Eddie Vedder -- what's-his-name -- dies along with two others.

So I'm glad for everyone's sake that that didn't happen.

AUSTIN SCAGGS

Posted Apr 21, 2006 4:39 PM